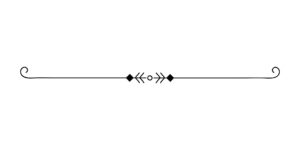

Chinese calligraphy is a highly esteemed art form with a rich history, reflecting the cultural and philosophical values of China. Here are some key aspects and styles of Chinese calligraphy:

Key Aspects

Cultural Significance: Chinese calligraphy is considered one of the highest forms of Chinese art, deeply connected to the language, literature, and philosophy.

Materials and Tools: The “Four Treasures of the Study” (文房四宝) include the brush (毛笔), ink (墨), paper (纸), and inkstone (砚). Quality and craftsmanship of these tools are crucial.

Techniques: Mastery involves control of the brush, understanding the flow of ink, and the rhythm of strokes. Calligraphers often practice for years to perfect their art.

Major Styles of Chinese Calligraphy

Seal Script (篆书): An ancient script with uniform and formal strokes, used for official seals and inscriptions.

Clerical Script (隶书): Developed during the Han dynasty, characterized by its broad and flat strokes, making it easier to write compared to the seal script.

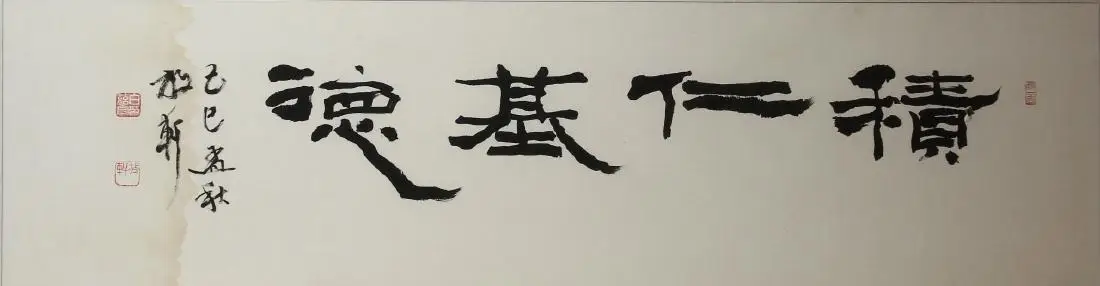

Standard Script (楷书): The most widely recognized script, known for its clarity and legibility, often used for formal writing.

Running Script (行书): A semi-cursive script that balances legibility and speed, commonly used for personal correspondence and informal documents.

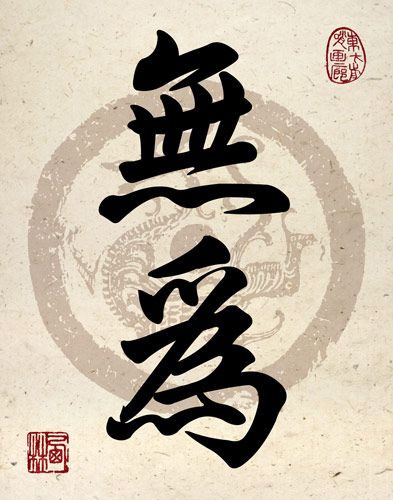

Cursive Script (草书): Highly stylized and abstract, valued for its expressiveness and dynamic flow, often used in artistic contexts.

Applications

Literary and Philosophical Works: Classical texts, poetry, and philosophical writings are often rendered in beautiful calligraphy.

Art and Decoration: Calligraphy is used to decorate scrolls, fans, and various everyday objects.

Modern Art: Contemporary artists integrate traditional calligraphy into modern and abstract art forms.

Learning Chinese Calligraphy

Traditional Training: Studying under a master calligrapher, often beginning with copying established works.

Workshops and Courses: Available in many art institutes and online platforms.

Practice and Patience: Continuous practice is essential for mastering the brush strokes and developing a personal style.

Notable Calligraphers

Wang Xizhi (王羲之): Known as the Sage of Calligraphy, his works, especially the “Preface to the Orchid Pavilion,” are highly revered.

Yan Zhenqing (颜真卿): Famous for his vigorous and robust style, contributing significantly to the development of the standard script.

Zhao Mengfu (赵孟頫): A versatile artist who contributed to the revival of classical styles during the Yuan dynasty.

Would you like to delve deeper into any specific aspect of Chinese calligraphy or explore the works of any particular calligraphers?

Key Aspects

Cultural Significance: Chinese calligraphy is considered one of the highest forms of Chinese art, deeply connected to the language, literature, and philosophy.

Materials and Tools: The “Four Treasures of the Study” (文房四宝) include the brush (毛笔), ink (墨), paper (纸), and inkstone (砚). Quality and craftsmanship of these tools are crucial.

Techniques: Mastery involves control of the brush, understanding the flow of ink, and the rhythm of strokes. Calligraphers often practice for years to perfect their art.

Major Styles of Chinese Calligraphy

Seal Script (篆书): An ancient script with uniform and formal strokes, used for official seals and inscriptions.

Clerical Script (隶书): Developed during the Han dynasty, characterized by its broad and flat strokes, making it easier to write compared to the seal script.

Standard Script (楷书): The most widely recognized script, known for its clarity and legibility, often used for formal writing.

Running Script (行书): A semi-cursive script that balances legibility and speed, commonly used for personal correspondence and informal documents.

Cursive Script (草书): Highly stylized and abstract, valued for its expressiveness and dynamic flow, often used in artistic contexts.

Applications

Literary and Philosophical Works: Classical texts, poetry, and philosophical writings are often rendered in beautiful calligraphy.

Art and Decoration: Calligraphy is used to decorate scrolls, fans, and various everyday objects.

Modern Art: Contemporary artists integrate traditional calligraphy into modern and abstract art forms.

Learning Chinese Calligraphy

Traditional Training: Studying under a master calligrapher, often beginning with copying established works.

Workshops and Courses: Available in many art institutes and online platforms.

Practice and Patience: Continuous practice is essential for mastering the brush strokes and developing a personal style.

Notable Calligraphers

Wang Xizhi (王羲之): Known as the Sage of Calligraphy, his works, especially the “Preface to the Orchid Pavilion,” are highly revered.

Yan Zhenqing (颜真卿): Famous for his vigorous and robust style, contributing significantly to the development of the standard script.

Zhao Mengfu (赵孟頫): A versatile artist who contributed to the revival of classical styles during the Yuan dynasty.

Would you like to delve deeper into any specific aspect of Chinese calligraphy or explore the works of any particular calligraphers?

-中國書法藝術欣賞-長安-Appreciation-of-Chinese-Writing-Brush-Calligraphy-Art.jpeg)

In ancient China, the oldest known Chinese characters are oracle bone script (甲骨文), carved on ox scapulae and tortoise plastrons, because the rulers in the Shang dynasty carved pits on such animals’ bones and then baked them to gain auspice of military affairs, agricultural harvest, or even procreating and weather.[clarification needed] During the divination ceremony, after the cracks were made, the characters were written with a brush on the shell or bone to be later carved

.01

Chinese bronze inscriptions

Main article: Chinese bronze inscriptions

Chinese bronze inscriptions were usually written on the Chinese ritual bronzes. These Chinese ritual bronzes include Ding (鼎), Dui (敦), Gu (觚), Guang (觥), Gui (簋), Hu (壺), Jia (斝), Jue (爵), Yi (匜), You (卣), Zun (尊), and Yi (彝).[14] Different time periods used different methods of inscription. Shang bronze inscriptions were nearly all cast at the same time as the implements on which they appear.[15] In later dynasties such as Western Zhou, Spring and Autumn period, the inscriptions were often engraved after the bronze was cast.[16] Bronze inscriptions are one of the earliest scripts in the Chinese family of scripts, preceded by the oracle bone script.

.02

Seal script

An example of the Chinese character 木 (a tree) written in Seal script

Seal script (Chinese: 篆書; pinyin: zhuànshū) is an ancient style of writing Chinese characters that was common throughout the latter half of the 1st millennium BC. It evolved organically out of the Zhou dynasty script. The Qin variant of seal script eventually became the standard, and was adopted as the formal script for all of China during the Qin dynasty.

.04

Clerical script

Memorial to Yueyang Tower by Fan Zhongyan, Song dynasty

Main article: Clerical script

The clerical script (traditional Chinese: 隸書; simplified Chinese: 隶书; pinyin: lìshū) is an archaic style of Chinese calligraphy. The clerical script was first used during the Han dynasty and has lasted up to the present. The clerical script is considered a form of the modern script though it was replaced by the standard script relatively early. This occurred because the graphic forms written in a mature clerical script closely resemble those written in standard script.[15] The clerical script is still used for artistic flavor in a variety of functional applications because of its high legibility for reading.

.05

Regular script

Main article: Regular script

Regular script (traditional Chinese: 楷書; simplified Chinese: 楷书; pinyin: kǎishū; Hong Kong and Taiwan still use traditional Chinese characters in writing, while mainland China uses simplified Chinese characters as the official script.) is the newest of the Chinese script styles. The regular script first came into existence between the Han and Wei dynasties, and was not used commonly until later. The regular script became mature stylistically around the 7th century.[17] The first master of regular script is Zhong You. Zhong You first used regular script to write some very serious pieces such as memorials to the emperor.[17]

.06

Ancient China

Chinese characters can be retraced to 4000 BC signs (Lu & Aiken 2004).

In 2003, at the site of Xiaoshuangqiao, about 20 km south-east of the ancient Zhengzhou Shang City, ceramic inscriptions dating to 1435–1412 BC have been found by archaeologists. These writings are made in cinnabar paint. Thus, the dates of writing in China have been confirmed for the Middle Shang period.[20]

The ceramic ritual vessel vats that bear these cinnabar inscriptions were all unearthed within the palace area of this site. They were unearthed mostly in the sacrificial pits holding cow skulls and cow horns, but also in other architectural areas. The inscriptions are written on the exterior and interior of the rim, and the exterior of the belly of the large type of vats. The characters are mostly written singly; character compounds or sentences are rarely seen.[20]

The contemporary Chinese character’s set principles were clearly visible in ancient China’s Jiǎgǔwén characters (甲骨文) carved on ox scapulas and tortoise plastrons around the 14th–11th century BCE (Lu & Aiken 2004). Brush-written examples decay over time and have not survived. During the divination ceremony, after the cracks were made, characters were written with a brush on the shell or bone to be later carved (Keightley, 1978). Each archaic kingdom of current China continued to revise its set of characters

chinese calligraphy

IMPERIAL chinese calligraphy

The earliest known Chinese logographs are engraved on the shoulder bones of large animals and on tortoise shells. For this reason the script found on these objects is commonly called jiaguwen, or shell-and-bone script. It seems likely that each of the ideographs was carefully composed before it was engraved. Although the figures are not entirely uniform in size, they do not vary greatly in size.

%

Oracle Script

%

Bronze script

%

-中國書法藝術欣賞-長安-Appreciation-of-Chinese-Writing-Brush-Calligraphy-Art-736x640.jpeg)

learn about over-art

learn about over-art

good pictures